Rectal Cancer

Treatment and Surgery in Delhi, India

-

What is rectum and rectal Cancer?

The rectum is the last part of our digestive system. One-third of colorectal cancers occur in the rectum. Rectal and colon cancer have similarities and are termed colorectal cancer, but there are critical differences. The rectum is enclosed in a small cavity called the pelvis. The rectal cancer could also be near the anal sphincter (the muscle ring responsible for holding the stools).

Four layers of tissue comprise the rectal wall. The innermost layer, called the mucosa, is where rectal cancer initially appears. Most begin as polyps, which are little lumps of flesh. Some of these polyps eventually transform into cancer, which spreads and grows.

-

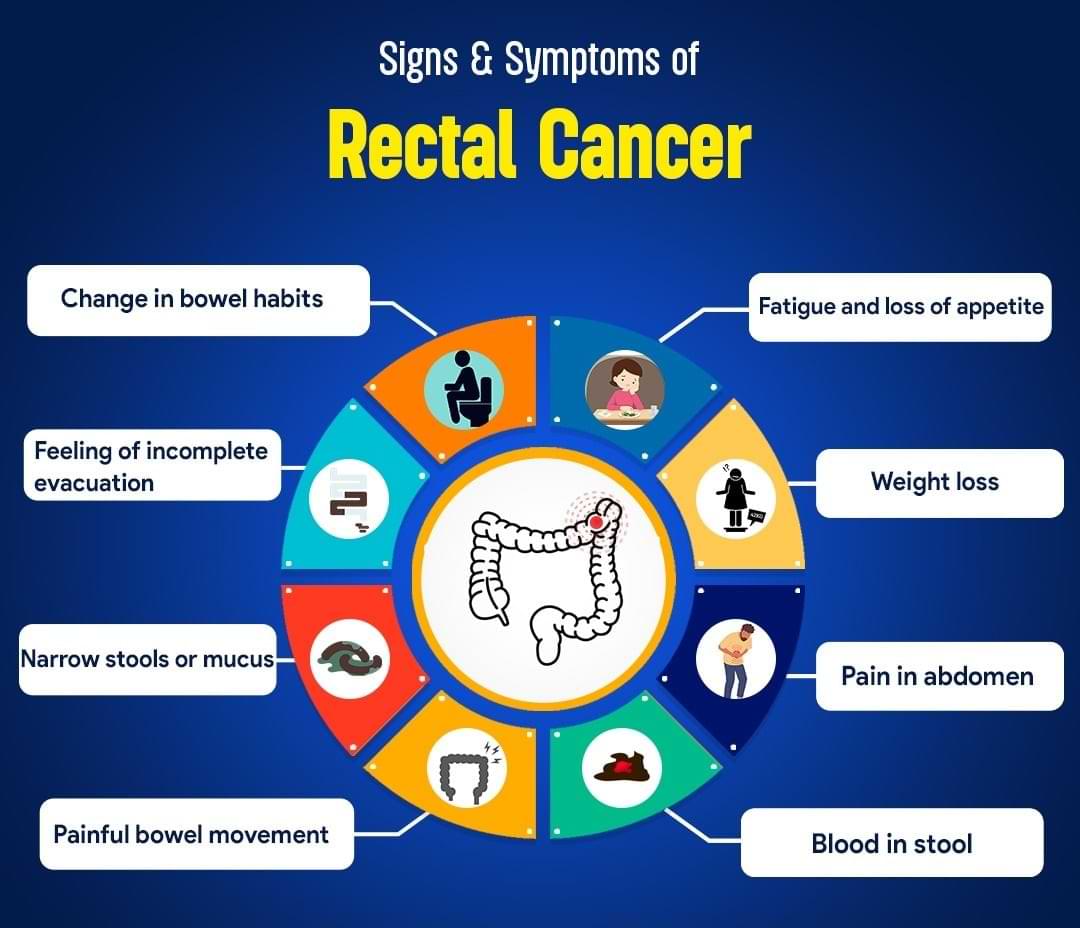

What are the signs and symptoms of rectal cancer?

Rectal cancer like most gastrointestinal cancers is asymptomatic in initial stages.

The symptoms of rectal cancer include:

- Blood in stool

- Change in bowel habits; persistent diarrhoea or constipation

- Feeling of incomplete evacuation

- Narrow stools or mucus in stool

- Painful bowel movements

- Unexplained fatigue and loss of appetite

- Unintentional weight loss

- Fall in haemoglobin (anemia)

- Pain or discomfort in abdomen

-

What are risk factors of rectal cancer?

Anything that increases the risk of someone getting cancer is a risk factor.

Risk factors for rectal cancer are:

- Genetic

- Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), also called Lynch syndrome

- Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)

- Western diet (high fat and low fibre diet)

- Older age

- History of colorectal polyps

- Family history of colorectal cancer

- Inflammatory conditions such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease

- Diabetes and obesity

- Smoking and alcoholism

- Genetic

-

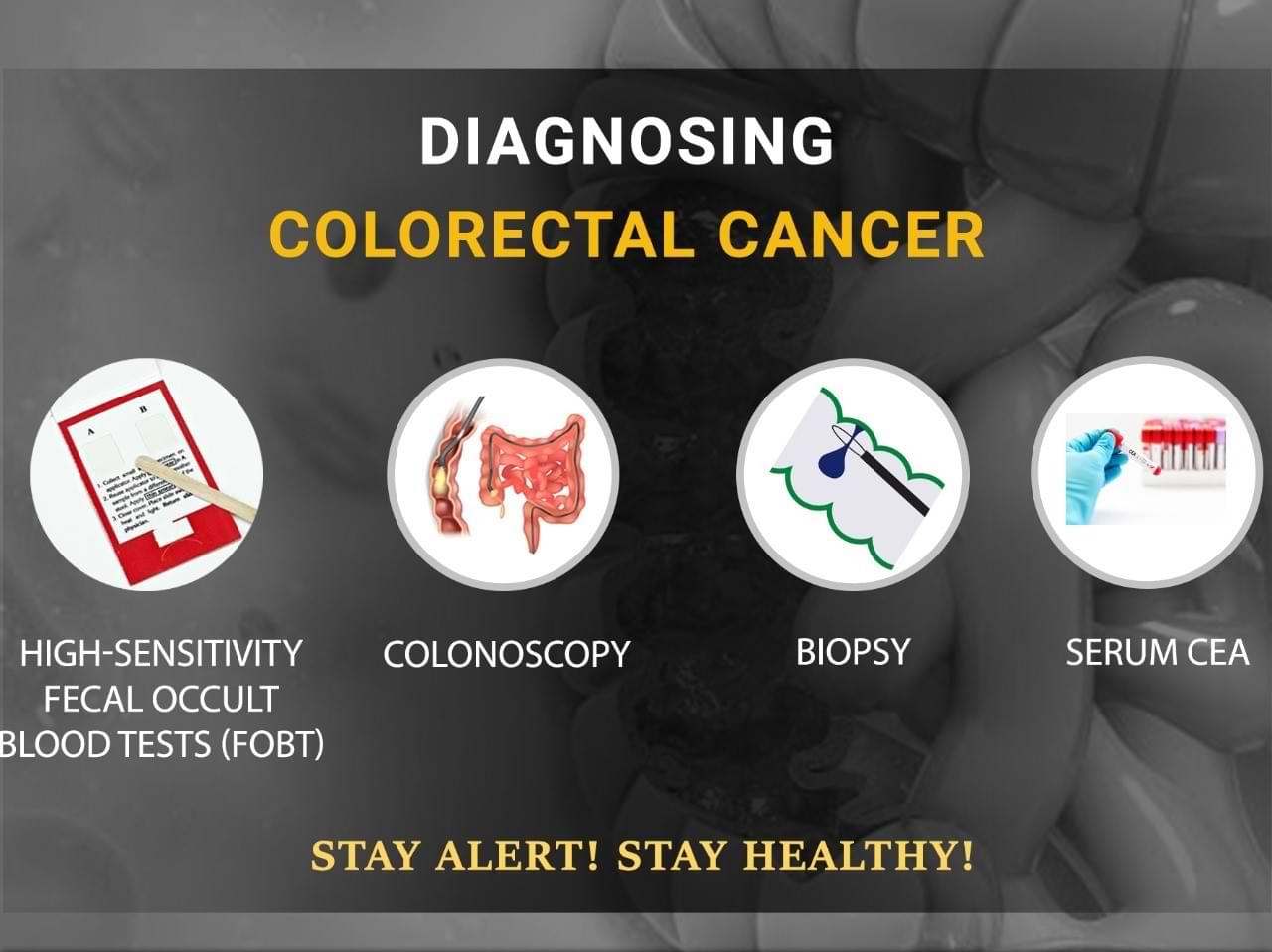

How is rectal cancer diagnosed?

The diagnosis of rectal cancer can be established through clinical examination and colonoscopy. Colonoscopy uses flexible camera to view the rectum from the inside. Biopsy and microscopic examination confirms the diagnosis.

Blood is also tested for CEA (carcinoembryonic antigen), which is produced by most rectal cancers.

-

How is rectal cancer staged?

Staging determines the disease's extent by assessing the size, location, involvement of adjacent organs, and spread to lymph nodes and distant organs.

Positron emission tomography (PET) or computed tomography (CT) scans are used for staging. For precise local staging, an MRI scan of pelvis is done.

-

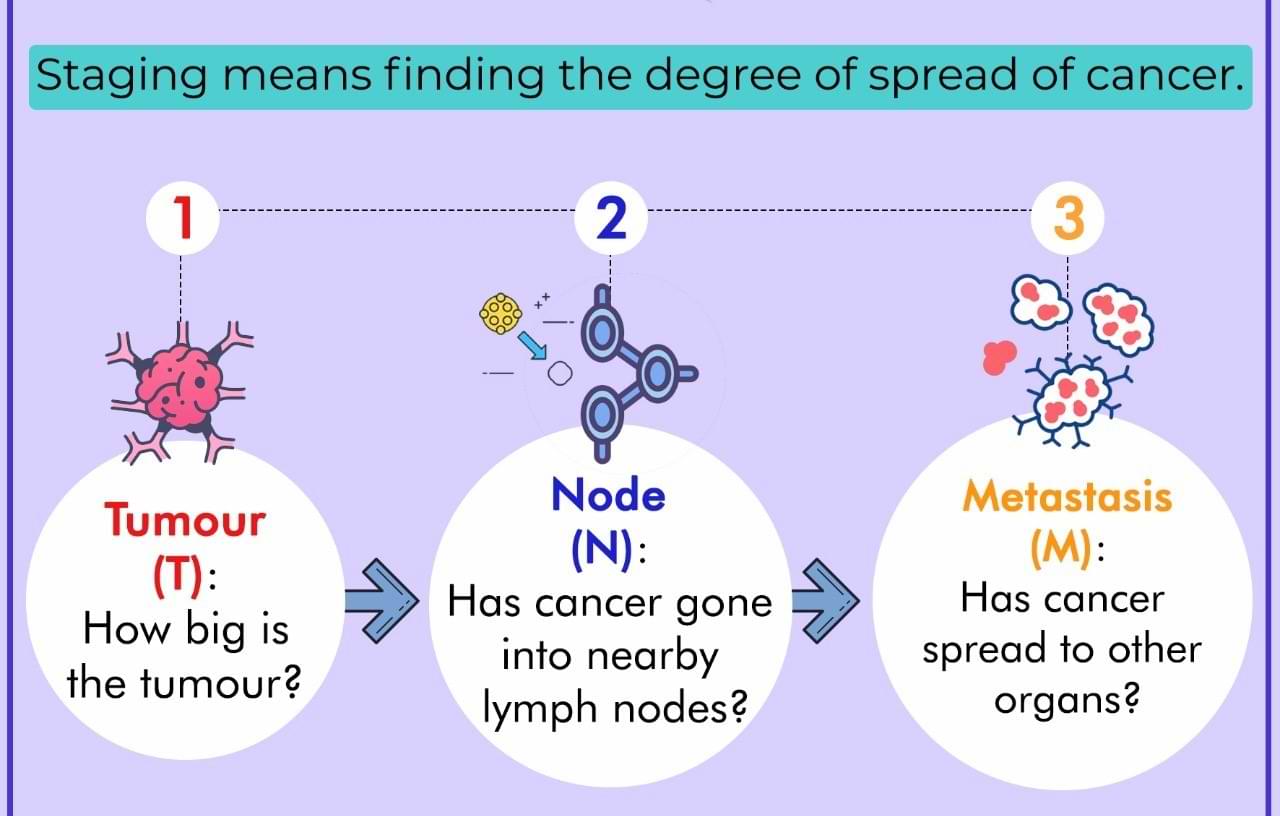

What is TNM staging for rectal cancer?

TNM (tumour, node and metastasis) classification developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) is used for exact classification of stage and it spans from I to IV.

- The extent (size) of the tumour (T): How far has the cancer grown into the layers of the rectal wall? Has the cancer reached nearby structures or organs?

- The spread to nearby lymph nodes (N): Has cancer spread to nearby lymph nodes? And to how many?

- The spread (metastasis) to distant sites (M): Has cancer spread to distant lymph nodes or distant organs such as the peritoneum or lungs?

-

How is rectal cancer treated?

An appropriate treatment is determined by the stage and location of the tumour in the rectum. The mainstay of treatment for people with localised cancer is surgery. Surgical resection of early tumours is done upfront.

Radiotherapy is the use of powerful X-ray beams to destroy cancer cells, and chemotherapy is the use of specific medications to do the same.

For advanced tumours, radiation and chemotherapy are used prior to surgery to provide the best results.

For metastatic rectal cancers chemotherapy and targeted therapy is used.

For MSI high (MMR deficient) tumours immunotherapy is more effective.

-

How treatment is sequenced in rectal cancer?

The sequence of treatment for a rectal tumor is determined by the tumor's extent, stage, location in the rectum, the involvement of adjacent organs, fascia, and the pelvic sidewall, the presence of disease elsewhere in the body, and the proximity to the sphincter.

Radiotherapy is preferably administered before surgery and can involve either a short or long course of radiation. It is usually combined with single-agent chemotherapy. Typically, doublet chemotherapy is administered after surgery.

For very advanced tumours, both radiation and chemotherapy (or immunotherapy) are used prior to surgery to provide the best results. This approach is called total neoadjuvant treatment (TNT).

-

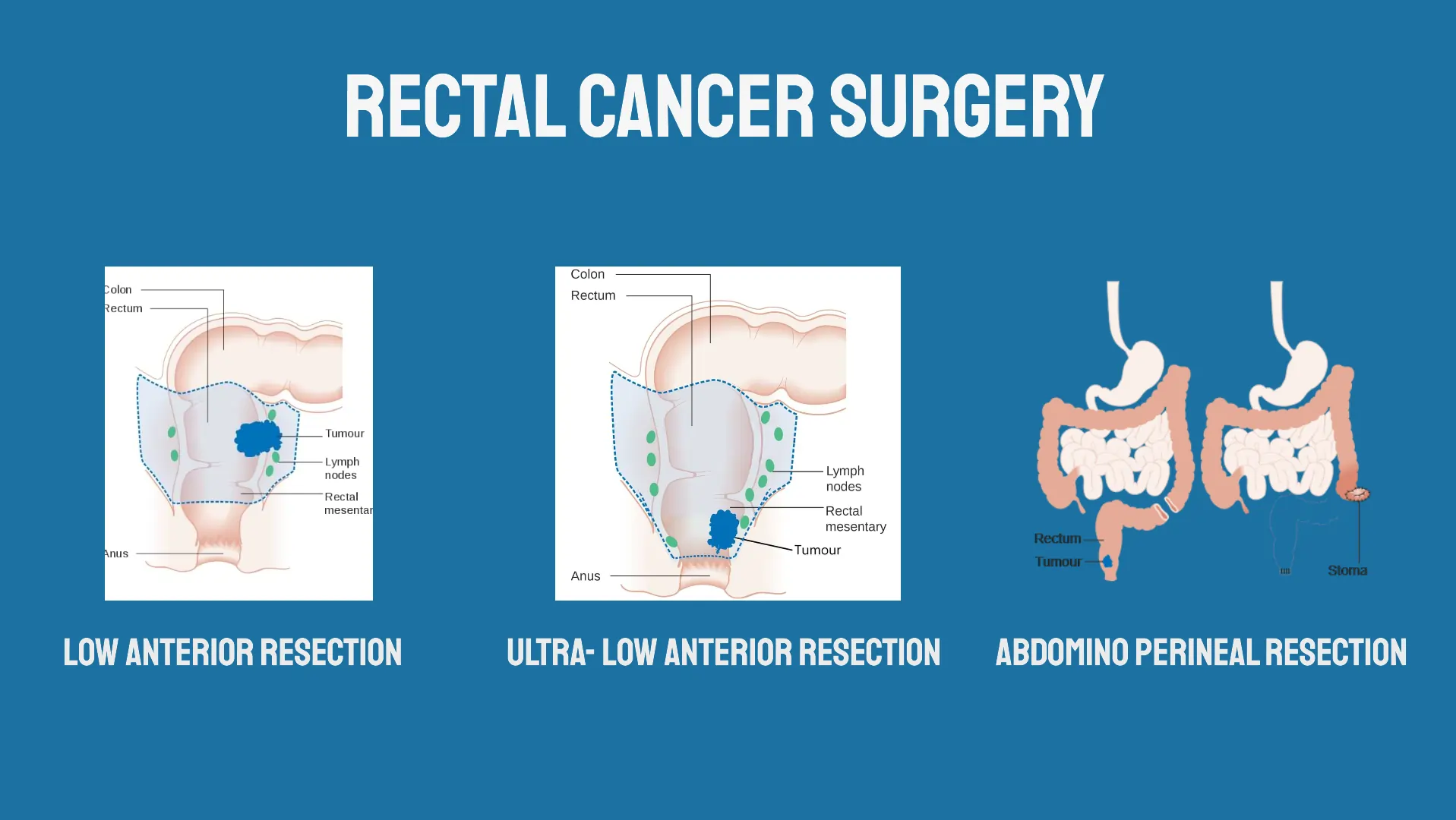

Which surgery is done for rectal cancer?

Surgery is the primary treatment for localised rectal cancer.

Rectal cancer surgery

- Transanal excision, transanal endoscopic microscopic surgery (TEM) and transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS)

- Anterior resection and low anterior resection

- Ultra-low anterior resection, proctectomy with colo-anal anastomosis, intersphincteric resection

- Abdominoperineal resection (APR)

- Pelvic exenteration

- Total colectomy (proctocolectomy)

-

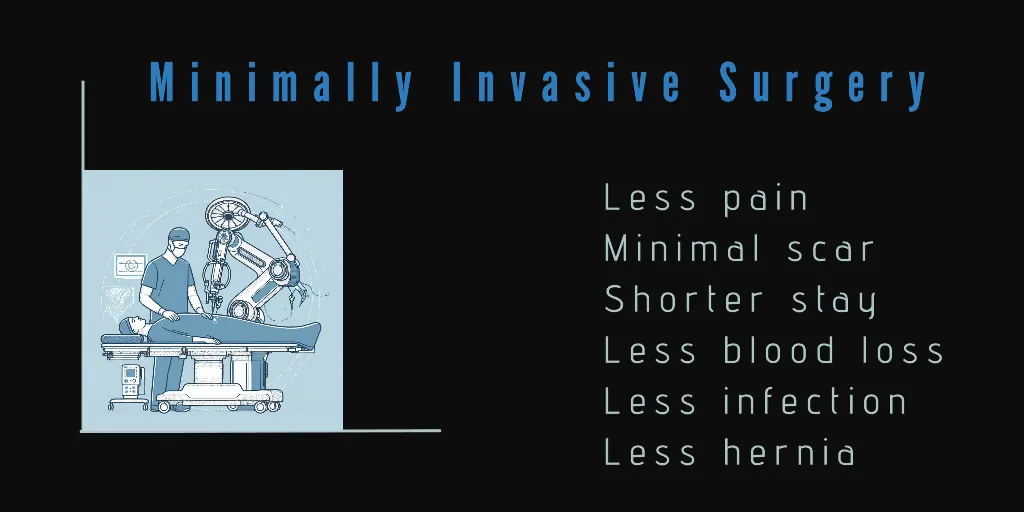

What are the benefits of minimally invasive surgery for rectal cancer?

In robotic surgery or laparoscopic surgery, we make a few small holes over the abdomen.

Minimally invasive surgery is beneficial for the patient in several ways. Post-operative stress and pain are markedly reduced, leading to a faster recovery and shortened hospital/ICU stay. The amount of blood loss in the process of surgery has decreased. There is a quicker return of intestinal movement. The overall complication rate is decreased. All this results in an earlier return to home and work.

-

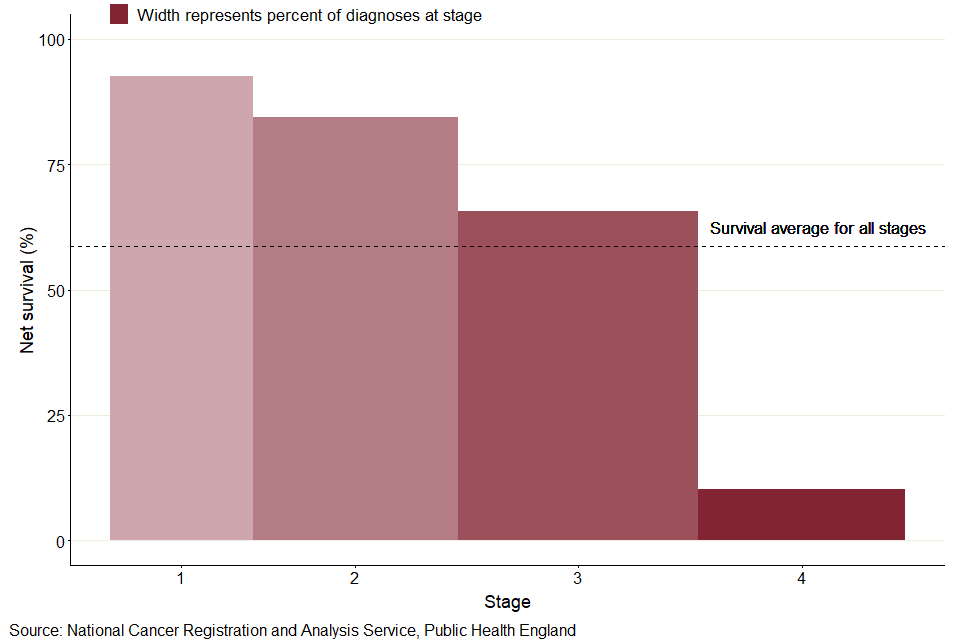

What are survival rates for rectal cancer?

It is often measured as 5-year survival. It is the percentage of people with the same type and stage of cancer who are alive 5 years after diagnosis and they can be considered cured. These estimates are generated from many patients. After treatment for stage 1 colorectal cancer, the 5-year survival is slightly over 90%. For stage 2 it is roughly 60–90%. The 5-year survival for stage III colorectal cancer varies from 45 to 90% and for stage 4, the 5-year survival is approximately 15%.

Wish you a speedy recovery!